Born Maria Anna Cecilia Sofia Kalogeropoulos in New York City in 1923, Maria Callas was, above and beyond everything else, a genius. Pushed early on to become a singer by a driving and harsh mother, she already showed tremendous promise by the time she was 10 years old. At only 13, she was entrusted to her main teacher, Elvira de Hidalgo, who passed on what was likely the last real Bel Canto training, a lost schooling that allowed Callas to interpret music in a manner that had largely vanished by the time she was born. She would go on to be an international superstar, the woman Meryl Streep called the 20th century’s greatest artist of any discipline, a fixture of front page news the world over. And despite crippling chronic health issues and personal tragedy – at the risk of sounding superficial – she looked pretty incredible through it all. Ahead of the release of Maria, Pablo Larraín’s painterly vignette of Callas’ final days, I want to look back at what made her image as enduring as her voice.

Blessed with large, expressive eyes, a prominent nose, and wide mouth, Callas’ own features made her innately arresting. She wisely played them up, especially her eyes, which she lined in a winged formation that became synonymous with her look. Her actual wardrobe saw a more pronounced evolution. Callas famously started her early adulthood in a larger body, likely due to hormone imbalances she experienced as a result of illness, before substantially trimming down after receiving treatment. She expressed a desire to match the slender, youthful physicality of the characters she played on stage, and once her health allowed her to do so, Callas dramatically transformed her off-stage life.

One of Callas’ first calls was to Italian couturier Elvira Leonardi Bouyeure, known professionally as Biki. Biki quickly created twenty-four fur coats, forty suits, 200 dresses, 150 pairs of shoes, 300 hats, and innumerable gloves that would form the foundation of Callas’ wardrobe. What’s clear is that from the beginning of Callas’ transformation, she heavily favored clean, well-tailored silhouettes that skimmed the body just so. Even when patterned or brightly colored, her clothes had a restraint that rendered them enduring against shifting trends.

As her career advanced and her reputation solidified, Maria Callas became a wealthy woman, one who knew how to exploit fashion to capitalize on her rising star power. Even more than that, fashion became a shield against relentless attacks from her peers and the press. Callas believed herself to be possibly the last in a great line of singers who had the immense training, artistic spirit, and sheer physiology to vocalize at the elite level required for the works of composers such as Bellini. The sound she produced was of a quality not heard since the 18th and 19th centuries, polarizing listeners. This coupled with her decisive artistic instincts and refusal to lower her standards put a perpetual target on her back from many of her contemporaries. The facade Callas created couldn’t afford to be anything less than flawless.

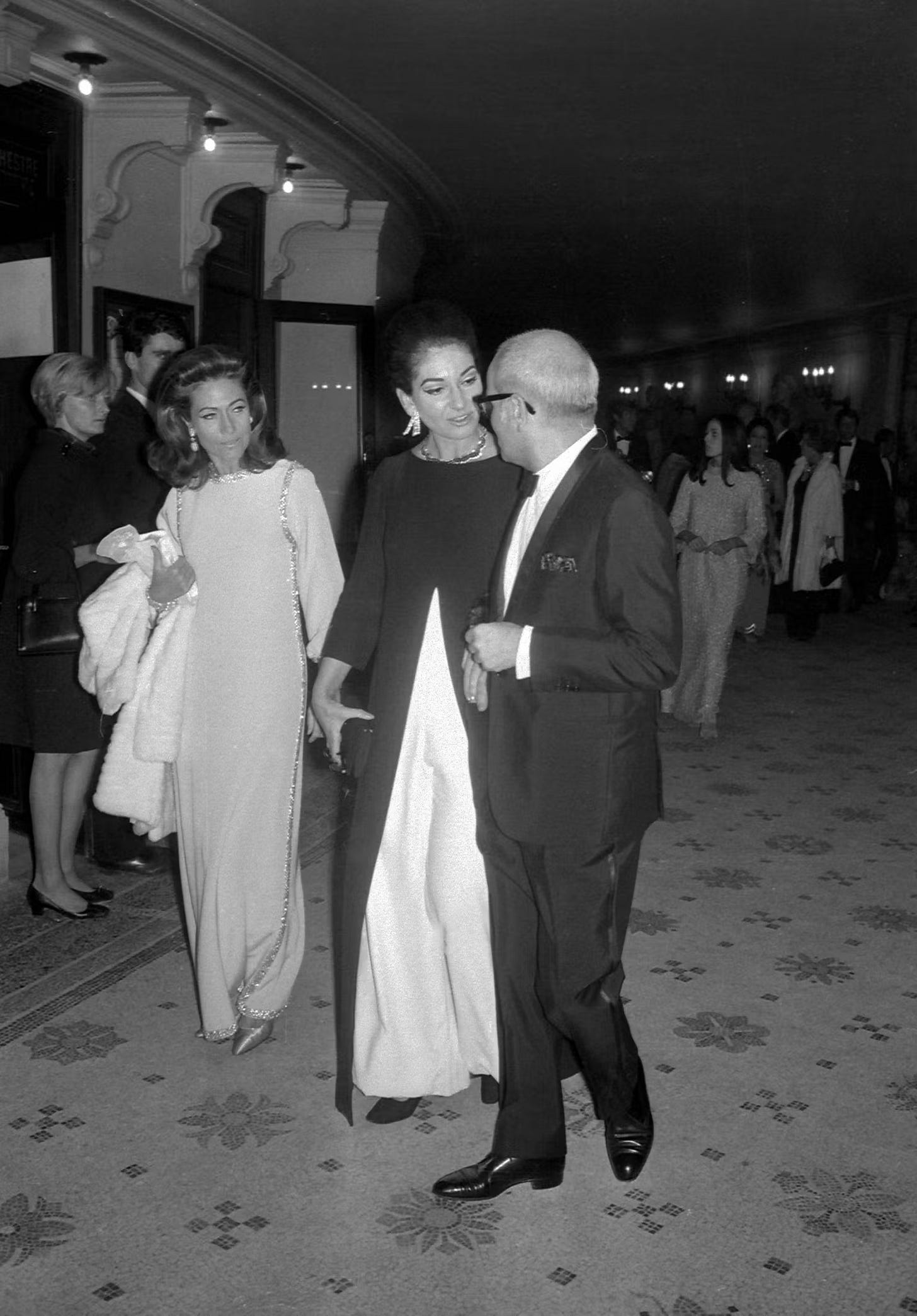

What began as the pursuit of elegance eventually turned into the embodiment of achingly impossible glamour. Perfectly coiffed hair, an elegant bag, a spattering of blinding jewels and couture became Callas’ standard, day or night. This was especially true when accompanied by her longtime lover, Aristotle Onassis, to a string of charity functions and international balls from the late ‘50s through much of the ‘60s (not counting the Jackie years, of course). Her style only became more defined as Callas befriended her share of great designers, including Yves Saint Laurent who ran in her same Parisian social circles.

But all of this was only possible due to that rarest of elements: good taste. No one talks about taste anymore, what it means, its power or its value. Maria Callas had it in spades. For her, it was sword and shield, a way to pour out into the world and sequester herself away from it when its demands became too much. She was only 53 when she died and like so many others taken at what seems to be far too young an age, it’s easy to wonder about what may have come next, the things she wanted to accomplish and that we as the public missed out on. Maybe Maria’s greatest lesson for us is the importance of giving everything you can – the best of what you’ve got, right now, unapologetically – and that such a way of being is its own reward.

I loved looking at Maria's gorgeous outfits, and as usual, wonder what colour many of them were? She was a fan of black, clearly, but also liked a bold large floral. That burgundy floral and the black floral dress are both so elegant.

I enjoyed the comments below regarding taste - and agree, that the constant search for the perfect aesthetic is akin to the development of taste...but without doing all the work of diving into design history, appreciating how things are made and crafted, and then seeing it all as a whole, and also as part of the fabric of life. I like to think I have good taste (don't we all!).

Another excellent article, Martin. I always look forward to yours.

god the shot of her on the phone in that black midi dress. I love it. Also love this paragraph: "No one talks about taste anymore, what it means, its power or its value. Maria Callas had it in spades. For her, it was sword and shield, a way to pour out into the world and sequester herself away from it when its demands became too much"

THEY DON'T TALK ABOUT TASTE ANYMORE. it's the hollow at the heart of so many conversations about aesthetics and fashion these days online. i think frequently about "quiet luxury", "stealth wealth" and how boring it is to reduce luxury (and the craft inherent in luxury, that is what draws me to it) to looking moneyed; similarly i know other commenters and creators on the internet have flagged that being drawn to "eclectic grandpa" is a desire for a life that has been lived and how simply looking like "eclectic grandpa" is valueless and will never capture the essence. i don't really blame the influencers though, i think so much of it is informed by the mediums through which we're creating these messages.

how can you talk about developing taste in an algorithmic world? i think taste is developed by a certain cultural literacy which is particularly hard to develop in this fracturing of media (and also of course, thinking about whose standards define taste? etc) and the cannibalization of culture by private equity companies.

(apologies for these scattered thoughts, thank you for pulling them out of me on this gloomy tuesday!)