NEW YORK FASHION WEEK IS IN A SLUMP. HERE'S WHY.

Once a vibrant fashion capital, New York is experiencing a lull like it hasn't seen in decades.

In a post-pandemic world, our idea of place is upended. Many of our social and work lives are made easier without the physical tethers to a specific location, a prerequisite for most of human history. But there is something to be said about the magic that can be contained within fixed boundaries – otherwise, there’d be no material difference between Madrid and Milwaukee. For 50 years, New York City has been one of four international fashion capitals, the one that ushered in the serious ready-to-wear and sportswear that’s come to dominate what we think of as ‘fashion.’ Where exactly it ranks in that roster has shifted more than once, but it has been decades since New York has seen the kind of creative downturn and disinterest it’s currently experiencing.

To remedy its unmoored state, it’s necessary to examine how New York Fashion Week got on the map in the first place.

By the late 1930s, New York was leading the way in the production of ready-to-wear clothes designed by a generation of homegrown talent that developed in tandem. And while New York was also home to a small coterie of designers working seriously in the couture mode during the same period – Jessie Franklin Turner, Elizabeth Hawes, Valentina Schlee, Charles James – the city as a whole was considered a fashion backwater compared to Paris.

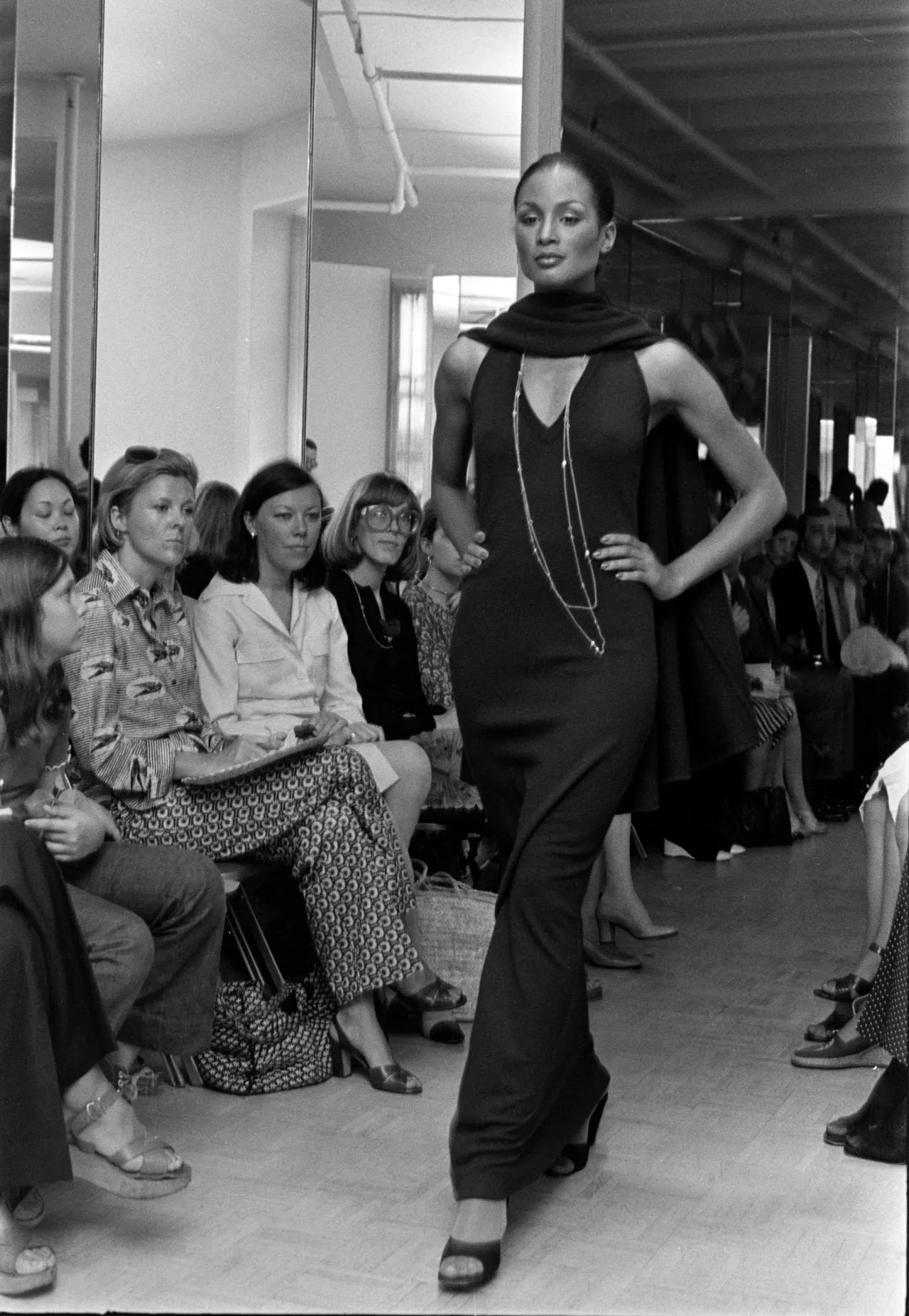

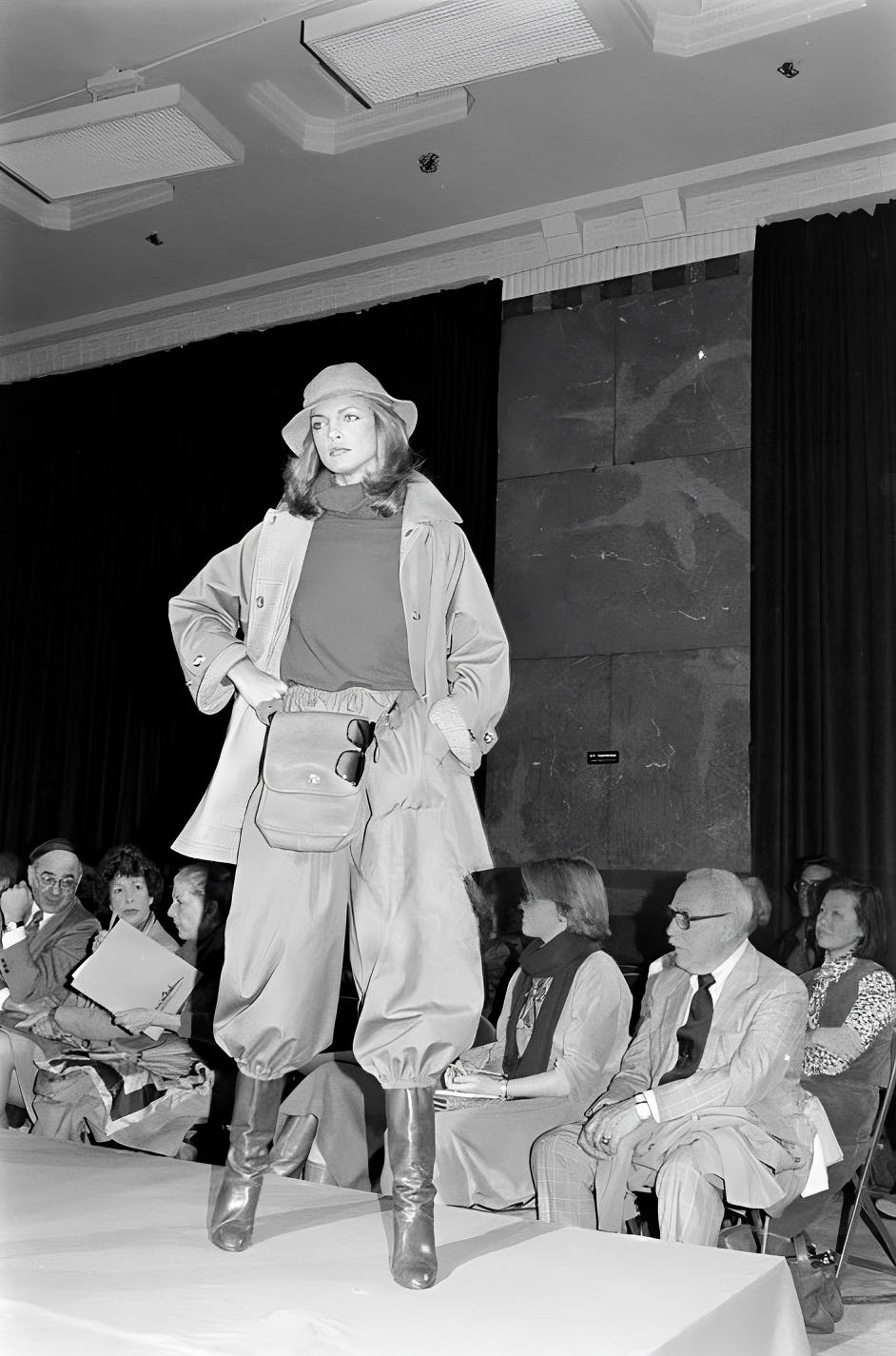

The Second World War proved pivotal for the American fashion industry. With access to Parisian designs cut off from 7th Avenue manufacturers, many of which (though not all) operated by producing sanctioned copies of couture originals, several previously anonymous and singular American designers were finally able to come out from behind the house labels they’d long driven. The subsequent 20 years saw a boom in New York’s fashion industry that inspired post-war Italy to create its own ready-to-wear business in New York’s image.

Throughout the mid-century, there was a distinct sentiment among American designers that bolstering their community and nurturing a unique American style and sensibility was paramount. But much as with the California wine industry that gained recognition decades later, it would take a head-to-head contest to really get the ball rolling. The brainchild of powerful publicist Eleanor Lambert, the fundraiser to support the restoration of Versailles, later known as the Battle of Versailles, pitted American designers against their esteemed French counterparts with the Americans coming out on top. [Dear reader: this event is covered in great detail in Robin Givhan’s book, The Battle of Versailles, and I highly recommend you read it and watch the documentary on the subject if you have the opportunity.] The resounding success incited a new appraisal of the work coming out of Gotham from the industry’s European wing.

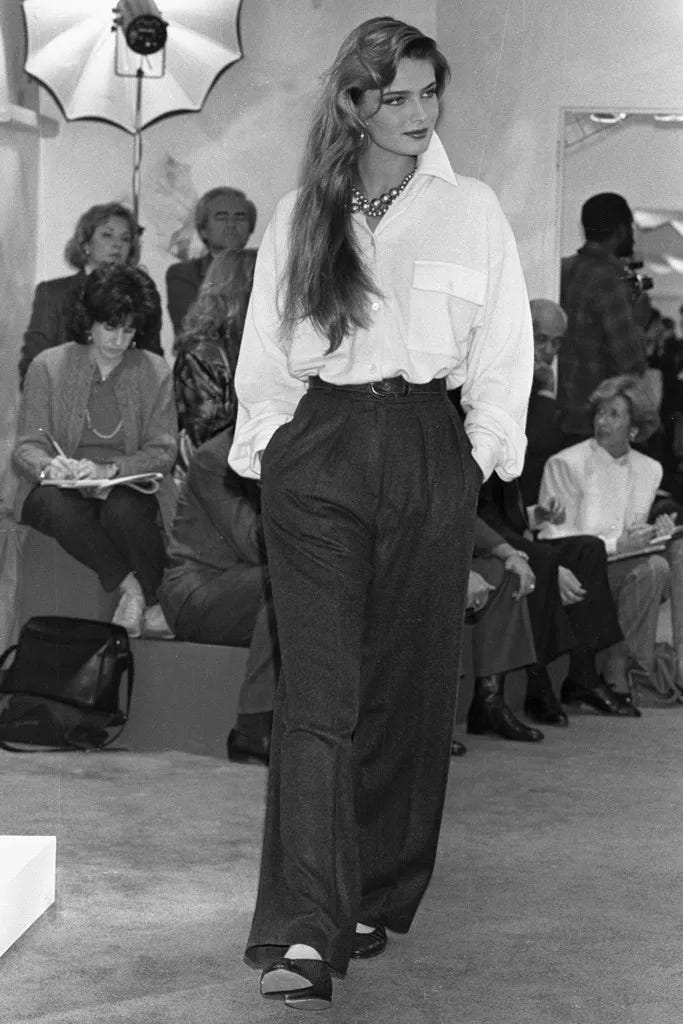

This wasn’t Lambert’s only coup. She spent most of her working life advocating for American fashion and spearheaded the idea of unifying what had been disparate collection showings into an organized fashion week. Her efforts paid off and by the 1980s, New York was booming with some of the world’s biggest mononyms, like Calvin, Ralph and Donna, who would continue to expand New York’s influence. Despite great global talent and fashion weeks in incredible cities like Tokyo, New York remains the only major international fashion week not based in Europe.

It’s difficult to say exactly where things went awry, but as with so much else, it’s a culmination of several factors. The first and most significant has to do with who’s showing. Beyond newness, fashion weeks function as venues for the strongest creative voices to communicate where they’re headed next and, by virtue of example, lead the pack. New York’s leaders have largely abandoned it to show in other cities and some of the biggest players who remain have chosen to show off schedule during unusual times of year. A number decamped to Paris for extended periods, including The Row, Proenza Schouler, Thom Browne, and others. The desire to up one’s creative game in such a competitive sandbox is a natural and understandable one. What’s disheartening is that there appears to be little collective interest from New York’s fashion community to keep pushing New York fashion forward as a whole. These days, The Row cosplays being French after spending its first decade-plus in business strongly advertising ‘Made in USA’ values. (A bit contrived, non?) Even the most New York of labels like Ralph Lauren have only had sporadic showings in the past few years. As with the headliners at any other event, the names of those in the lineup are an inherent part of the draw with a halo effect that boosts new or developing designers. It must also be mentioned that the schedule ballooned enormously at one point with names I don’t believe are ready or worthy of being included, the effect diluting the entire week.

The second biggest factor is location. NYFW was neatly consolidated into the tents at Bryant Park for years and the ease of having most shows in one location can’t be understated. The aforementioned swelling of the calendar meant that the tents became untenable as the volume of shows increased. Lincoln Center was offered as an alternative for a time, but its out-of-the-way locale mixed with broader disorganization led brands and members of the fashion press to quickly abandon it. This only served to enhance an underlying sense that there was no focus to the undertaking overall with shows once again scattered throughout the city.

My third point might be more controversial. Throughout the aughts and early teens, New York acted as a foil to Paris’ legacy houses by debuting new designers, a factor frequently cited as one of its primary draws. Regardless of what I may think of them, what they create, or how they run their businesses, the likes of Proenza’s Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, Joseph Altuzarra, Alexander Wang, and Jason Wu all emerged in rather rapid succession going on to build substantial brands with international stockists, major ad campaigns, and weighty appointments to other houses. I don’t want to in any way suggest that the talent pool has dried up, but it is different. Brands like Luar have a loyal following but remain significantly more niche than their predecessors. The reasons for this are myriad and, frankly, deserve their own newsletter. Ultimately, fashion is a business and it will only turn its attention toward and pour its resources into smaller labels for so long.

And yet, things can turn around. New York, London, Milan and yes, even Paris, have all gone through bleak periods. A concentrated and concerted effort is required to change that. It’s really only a question of whether or not New York – and its leadership – still has the will to make it happen.

I just love your writing and I’m a newish student of fashion history (10 years, maybe more, since I started reading bios and books about fashion history). I loved The Battle of Versailles and watched the documentary-I foisted the book on my Book Club, and showed them my treasured Stephen Burrows disco top. 💕

We just spent 4 days in Milan the past week. Two things really stood out.

First of all, luxury fashion brands are spending big time on new shops all over the Quadrilatero. They are really investing in getting the best visibility for their brands whatever the cost. The same happened in Paris in 2021. It creates a dynamic that puts those cities on the map for their fashion weeks. We spent a month in NY in May, and we didn't see anything similar in Manhattan.

Secondly, there are no American brands to speak off. RL's shop is a shadow of its former self. Thom Browne's shops are... well, like Thom Browne's shops anywhere else.

Becoming the world's fashion capital for a week needs more that what NY has to offer at the moment.