PIETER MULIER DOESN'T UNDERSTAND ALAÏA

The house's current designer works in service to his aesthetic–but not to women.

Dramatic as it may sound, when Azzedine Alaïa died in 2017, I think fashion went with him. Yes, people would continue to make and present clothes, but the age of aspiring to good taste, committing to craft, and looking to the past to evolve toward the future was over. Alaïa was a great designer, one of the greatest and most technically astute of all time. No reasonable person could expect Alaïa’s successor to be anything more than a faithful steward of that singular legacy, one who could intelligently move things with the times and bring their own sensibility while remaining true to the Alaïa ethos. If only that were the case.

Pieter Mulier, the longtime right-hand of Raf Simons, was charged as creative director, and since his debut runway show two years ago, his take on the brand has unsettled me. Mulier’s version of Alaïa has been lauded, even being embraced by Vogue and Anna Wintour who blacklisted Azzedine for decades for his refusal to play ball and do anything other than speak his mind. But Mulier’s efforts are hollow and peripheral, his designs shadows that have mistaken themselves for the sun. Worse yet, Mulier’s Spring 2025 showing in New York City’s winding Guggenheim Museum only served to cement that his Alaïa is in no way true to the founder’s most sacred principles.

Among Mulier’s more daring attempts with this show was an excavation of the designers Alaïa himself deeply admired and was inspired by, chiefly Charles James and Madame Grès (I have it on good authority that Alaïa had more than 900 examples of Grès’ work in his private collection at the time of his death.). Guests witnessed oversized interpretations of James’ iconic eiderdown coat (the first-ever puffer coat) and numerous iterations of dresses inspired by Grès with dense pleats rendered to mimic her much more complicated fluting techniques as well as airy, gathered details that mirrored her use of silk paper taffeta. What was so disappointing is that, unlike Alaïa himself, Mulier did nothing meaningful to modernize or subvert these styles. And they certainly don’t look any better. Mulier simply name-checked the masters, ticked the ‘reference’ box and kept it moving.

In fashion, there is a lineage of great design, a line of gifted and innovative creators who changed how garment construction was understood and how we dressed in the process. Azzedine Alaïa knew this well – and is unquestionably a part of it – as besides his brilliance as a designer, he was also a ferocious researcher and student of fashion history, a passion that undoubtedly buoyed his remarkable talent. He opted to study the innards of garments produced by his noblest predecessors rather than be satisfied with a superficial understanding of their work. These were not images on a mood board for Azzedine so as much as they were blueprints of genius worthy of examination and reconstruction in a new manner. Mulier uses homage in service of concept while Alaïa used homage in service of the woman wearing his clothes. The latter was perhaps the most distressing deficiency of the Spring presentation.

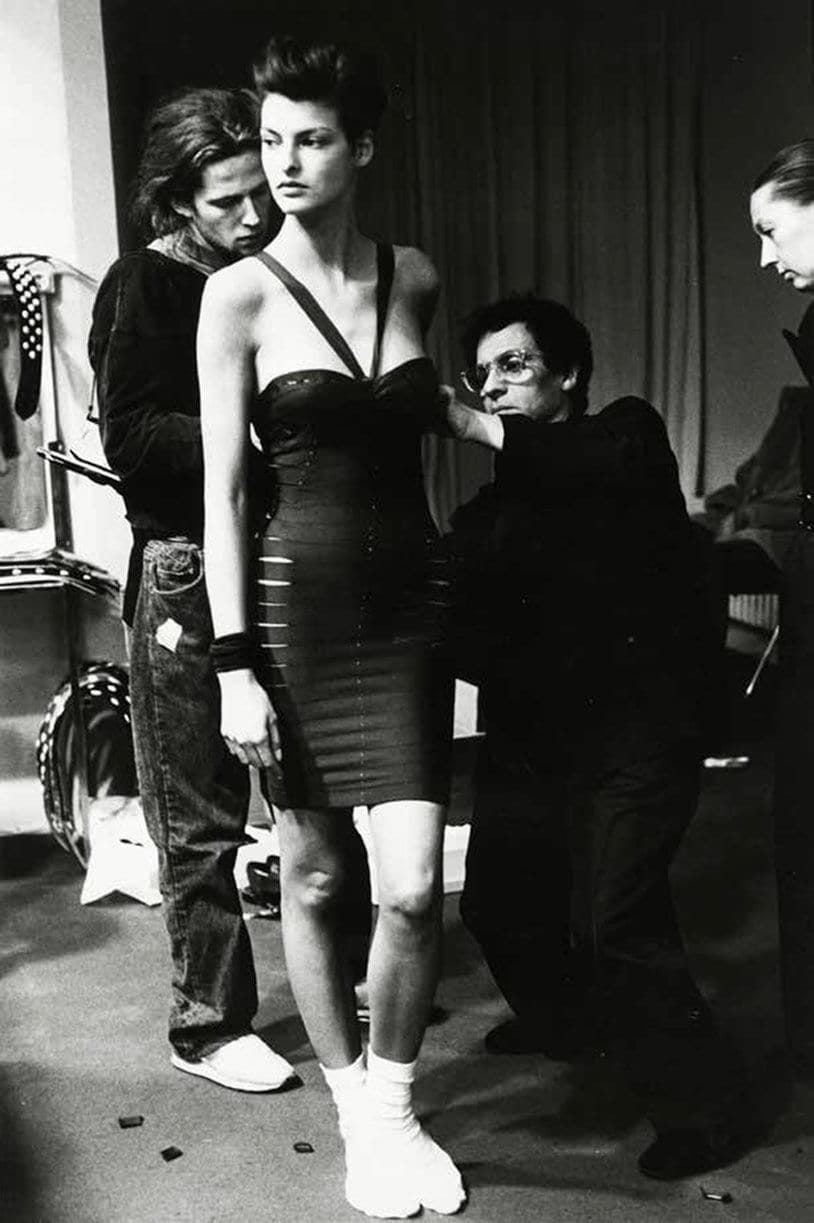

Alaïa was no stranger to a midriff or a slash of thigh or a strategically hoisted bust. The critical difference is that in Alaïa’s hands, those elements were not meant to expose but to enhance. His work was unapologetically sensuous not because it was designed with the sole intention of attracting romantic attention but because Alaïa spent a lifetime fitting, patternmaking and sewing to learn how to honor women’s bodies to the utmost. There was nothing precarious about Alaïa’s designs. One never had that gnawing, hold-your-breath feeling that something was about to slip out. He offered security to his clients in more ways than one.

None of that applies to Mulier’s work for the house. Where Alaïa’s knits doubled as sculpting shapewear, holding in and releasing in the most flattering way possible, Mulier’s spread apart like loose crochet assuming the wearer’s flesh will do all the work. Where Alaïa would meticulously fit a garment of any material so it fell properly no matter which way its inhabitant moved, Mulier overly relies on stretch resulting in clothes that people fit into but never truly fit.

As a whole, Mulier’s clothes skew heavily toward youth and one body type, both antithetical to Alaïa’s ideals. In a real Azzedine show, one could see nearly every kind of woman: the woman who wanted something erotic and daring with a snatched waist and plunging neckline; the woman who sought something feminine and light but felt more comfortable covering her upper arms – without it ever looking like that was her intention; the woman who preferred traditionally masculine styles and boycotted the dresses for incredible sculpted blazers, crisp poplin shirting and oversized trousers; and so, so many others. Alaïa was able to carve out these many facets because he was constantly looking to the women he interracted with, clients whose concerns, needs, and desires he absorbed with utmost seriousness and executed with as much dedication. Alaïa conducted every fitting for every client himself. “When you look after clients, that’s how you learn,” Alaïa once told editor Carine Roitfeld. “Because if you don’t see how a design is worn or what women want or how they want to wear it, you’re just designing in a void. And that isn’t good.”

Mulier’s narrow and impractical vision is best exemplified by a series of top-skirt sets and pleated dresses sprinkled throughout the show. The former plays on Mulier’s recent fascination with spiraling silhouettes by forming tops that wrap around from the back. These were paired with skirts that hugged the hips before descending into an awkward puffer formation (I guess one wants to ensure their lower legs are warm while wearing a bandeau?). Yet it is the dresses I find most offensive. Pleated in a style suggesting Madame Grès, Mulier took the elegantly erotic cutouts Grès so often experimented with and used them to gouge a canyon of flesh clear through the front of each dress. I adore sensuous clothes, but these were vulgar – a line Alaïa himself never crossed – and ill-fitting with no appreciation for what it would mean to move in those garments or that they made the models look twice as wide. These were (ugly) clothes for show, not for life. That is not what Alaïa represents.

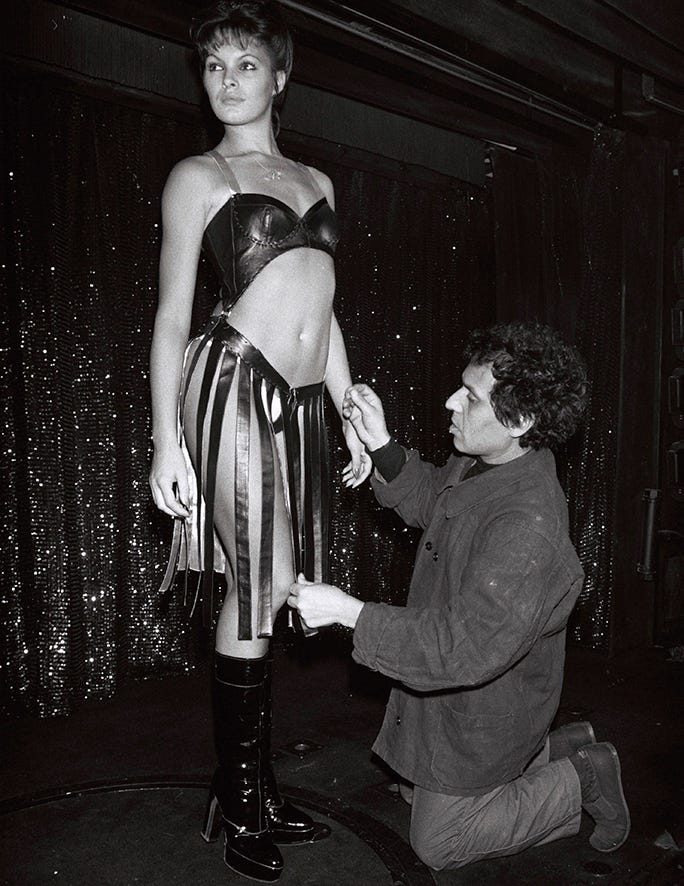

Taking it all in, I kept thinking of a line the critic Cathy Horyn said in a short documentary on Alaïa directed by stylist Joe McKenna. “I didn’t know that he had designed garments for the girls at The Crazy Horse. And I thought, ‘God, if you have to get in there and really measure those women, you’re really not worried about women. You’re not intimidated by them and you don’t have any fantasies about them.’ And that, we all know, is a problem with many designers, male or female. They have a fantasy about women that doesn’t jive with reality.” Mulier should take note.

I never knew Alaïa, but I miss him terribly.

Thank you for this post, I couldn’t agree more! Everyone has missed the point that Alaïa honored women with clothes real women actually wore. I did a post on him a month or so ago. He was the last of the greats.

What a text. Bravo!